"There on the beaches of Normandy, I began to reflect on the wonders of these ordinary people whose lives are laced with the markings of greatness. At every stage of their lives they were part of historic challenges and achievements of a magnitude the world had never before witnessed."

— Tom Brokaw, “The Greatest Generation,” 1998

My dad admired Tom Brokaw. They never met, but they were of the same time and place. About the time Brokaw was in high school in Yankton, South Dakota, Sanford Olson was dating his soon-to-be wife with sundaes at an ice-cream parlor across the street from her college a few blocks from Yankton High School.

A devotee to NBC’s “Huntley and Brinkley” newscasts in the 1960s, Dad followed and embraced Brokaw’s rise to the top of TV journalism. My dad died six years into Brokaw’s 22-year run as NBC’s anchor, but the connection remains. He was proud of a guy he never met.

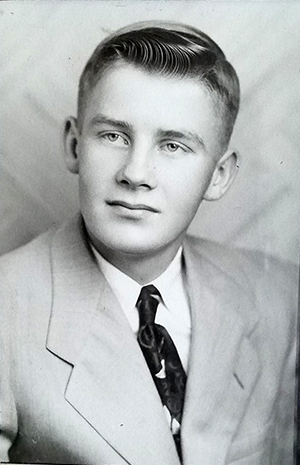

I consider my dad (shown at left) part of “The Greatest Generation,” the tag Brokaw gave World War II veterans in his book of the same name. Dad wasn’t a part of WWII; he went to Korea eight years after WWII ended. He didn’t storm a beach; he was a military police officer. But what happened to him there changed his life.

I consider my dad (shown at left) part of “The Greatest Generation,” the tag Brokaw gave World War II veterans in his book of the same name. Dad wasn’t a part of WWII; he went to Korea eight years after WWII ended. He didn’t storm a beach; he was a military police officer. But what happened to him there changed his life.

Also among the greatest generation was Michael Rahal, whose son Bobby went on to win the Indianapolis 500 and three Indy car championships. Together with son Graham, the Rahals account for 31 Indy car victories. Michael Rahal and two brothers fought in the Pacific theater during WWII. He died earlier this year at the age of 93. Last month, he was interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

While talking to Bobby and Graham last week for a Veterans Day story, I kept looking at the flag that covered my dad’s casket when he died in 1988 at the age of 54. It sits here on my desk in a wood-and-glass case (shown below left), a daily reminder of his sacrifice and struggle.

Years after his death, I heard the term post-traumatic stress disorder for the first time. Immediately, I understood what happened to my dad. The smoking and drinking that became the throat cancer that killed him was a direct result of his time in Korea.

Men of the greatest generation didn’t seek help. They didn’t complain. Their demons were hidden, their problems never discussed. They were tough, often too tough for their own good. I rarely saw my father without a cigarette. I rarely saw him laugh uproariously. I never saw him cry.

The drinking was always there. When I was young, our Saturdays involved a drive to Beaverdale, a neighborhood not far from our church. We’d get haircuts, go to the hobby shop and spend my allowance on the latest Matchbox car or 1:24 scale plastic model. Then we’d stop by the bar, where he had a screwdriver while I’d have a Coke. I was sworn to secrecy. It was dangerous fun for an 8-year-old kid.

When I was 18, my mom and I carried Dad to the car and took him to the hospital. He hadn’t had a drink in days, but he couldn’t get out of bed. As he began the detox process that night, he started talking about Korea. I had never heard any of it. For 25 years after Korea, my dad had punished himself for what happened there.

Eventually, he found sobriety. It took more than one attempt, but he found it. Strange as it sounds, his best days came when he knew he was dying. Surgery had required a tracheotomy. The surgeon managed to save his vocal cords, but his breaths came through a hole in his throat. He bought a sports car. When I think of my father, I see him in that car, half his neck gone, hole in his throat, smiling with abandon.

Had it not been for his interest in newspapers, in reading and in cars, I wouldn’t have stumbled down this career path. Just as Michael Rahal’s service as chief torpedo man on the USS Macdonough was the foundation for what the Rahal family became, so, too, was my dad’s service the foundation for what I became and what he never saw. The greatest generation sacrificed not just for their country, but for their children. Without them, we’re not here. None of this has happened.

Had it not been for his interest in newspapers, in reading and in cars, I wouldn’t have stumbled down this career path. Just as Michael Rahal’s service as chief torpedo man on the USS Macdonough was the foundation for what the Rahal family became, so, too, was my dad’s service the foundation for what I became and what he never saw. The greatest generation sacrificed not just for their country, but for their children. Without them, we’re not here. None of this has happened.

Days before he died, my dad heard that I’d been hired full-time by the same newspaper he'd helped me deliver on snowy Sunday mornings when I was 12 years old. I’d been part-time in the sports department for six years, waiting for my chance. He was thrilled by the news. A few years before that, he’d made a trophy of my first bylined story, a few column inches about a high school basketball game. He burned the edges of the newsprint with a lighter, glued it to a smooth piece of cedar and varnished it.

He never knew that his son went on to cover the Indianapolis 500 a few dozen times. He would’ve loved that. He finally would’ve seen the race he followed only by radio, magazines and newspapers. He would’ve seen his daughter attain a master’s degree. He probably would’ve bought another sports car and continued to smile with abandon into old age.

Every family has been affected – either directly or indirectly – by this generation of people who served their country quietly, bravely and steadfastly, then returned home to start careers and families. They saved this country, then watched over its remaking. Without them, the success of their descendants doesn’t happen. They were the fortunate who came home, and we are the fortunate who continue to benefit from their selflessness.

Ordinary people whose lives are laced with the markings of greatness. We’re here because of them, and we’re better because of their service. That’s truly something to admire.